Ocean Alive responds to the problem of seagrass meadow degradation in the Sado estuary. The rapid depletion of this habitat has led to scarcity of marine life and contributed to unemployment and devaluation of the fishing community (namely the fisherwomen), as well as to the declining of the resident dolphin population.

WHAT ARE SEAGRASS MEADOWS?

Seagrass meadows are habitats made by aquatic plants - seagrasses - which form a complex rhizome system in coastal areas, lagoons and estuaries.

Seagrasses are vascular plants. Unlike algae, they have roots, stems and leaves, and the ability to produce flowers, fruits and seeds. They belong to the “flowering plants” group (angiosperms) and evolved from terrestrial ancestors about 100 million years ago.

Usually, seagrasses occupy only shallow waters. Depending on each species’ characteristics, they occupy intertidal (which become uncovered by seawater at lower tides) and subtidal zones (always covered by seawater). Like any other plant, they only survive at a depth with enough light penetration to perform photosynthesis, at a maximum of ~70 meters in clear water, and only ~10 meters in Sado estuary, since it is a transition zone between the river and the sea where water is naturally more turbid.

1. Zostera marina ©C.A.M.Lindman | 2. Zostera noltei ©Walter Müller | 3. Cymodocea nodosa ©Nuno Farinha

WHERE ARE SEAGRASSES LOCATED?

Seagrass meadows are found in every continent, except Antarctica. Here you can find a map of their global distribution.

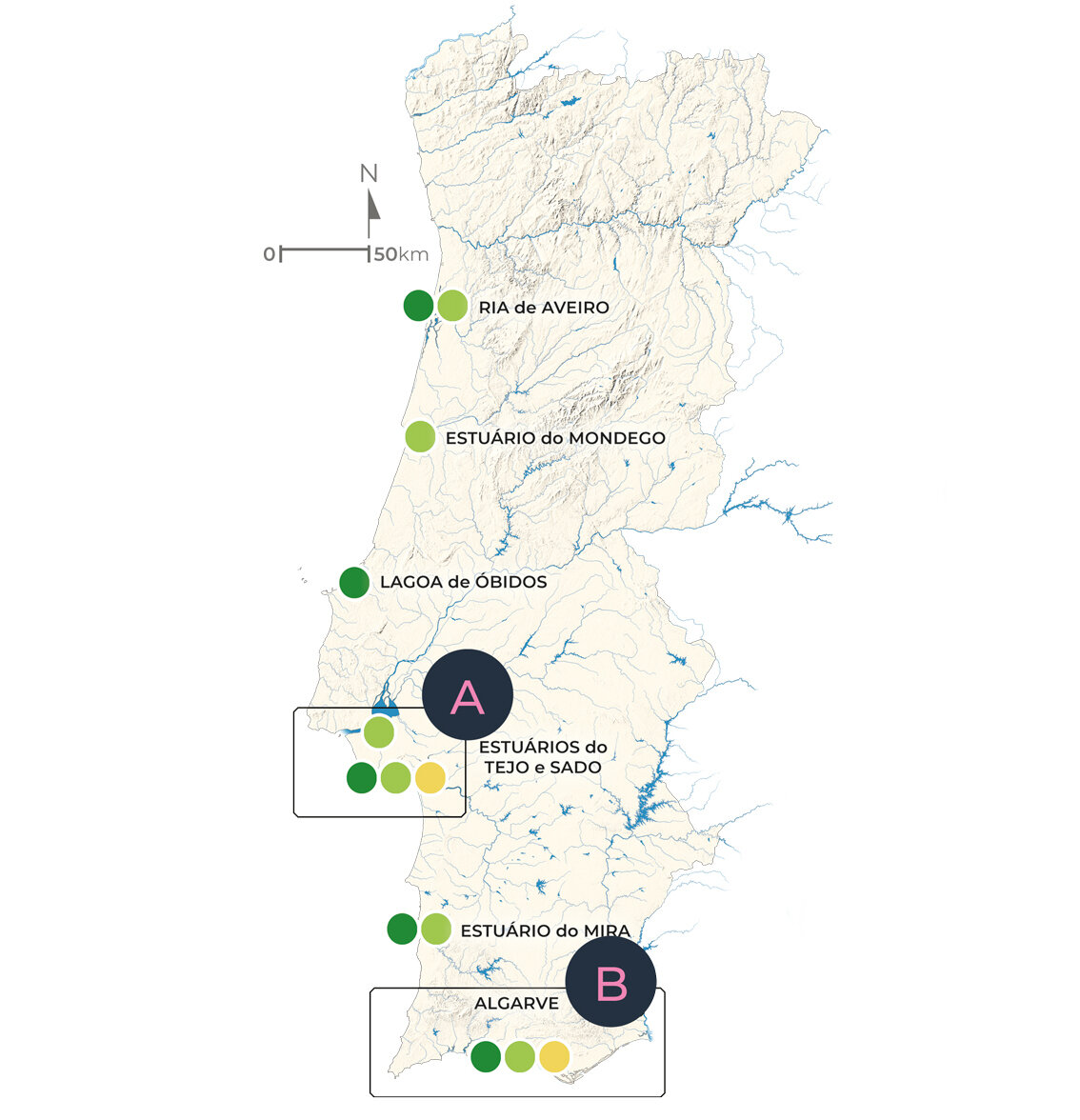

In Portugal, seagrass meadows are found in Ria de Aveiro, Lagoa de Óbidos, Ria de Alvor and Arade, Ria Formosa, Mondego, Tagus, Sado, Guadiana and Mira estuaries, sheltered bays on Arrábida and Algarve coast, and Madeira island. Ria Formosa is where the biggest cover area is registered. A national estimate points to a total area of 1690ha (1), but an updated evaluation is needed. The only places where the simultaneous occurrence of the 3 species present on the portuguese coast - Zostera marina, Zostera noltei and Cymodocea nodosa - is documented are the Sado estuary and the Ria Formosa.

©Nuno Farinha / Fonte: Cunha et al 2011

Seagrass meadows contribute to our survival and well-being.

Seagrass meadows offer us a number of ecosystem services: a set of natural processes which directly or indirectly contribute to human well-being.

Fisheries

Seagrass meadows support fisheries and are the nursery habitat of commercial species (fish and shellfish)

Climate regulation

They sequester and store high amounts of carbon in their biomass and sediment, which helps to mitigate climate change

Disease control

They reduce pathogen exposure for humans, fish and corals

Biodiversity

Hotspots of marine biodiversity, including protected and charismatic species such as seahorses, turtles, dugongs and sharks

Coastal protection

They prevent coastal erosion and protect the shore from storms and floods

Water purification

They are natural filters, retaining the sediments and removing excess nutrients from the water

Tourism

They provide cultural services which are linked to the communities’ identity and give opportunities for recreational activities such as birdwatching, scuba-diving and fishing

MARINE NURSERY HABITATS THAT SUPPORTS BIODIVERSITY, COASTAL COMMUNITIES AND THE FISHING ECONOMY

Seagrass meadows are important nursery areas for fish and invertebrates, from eggs to larvae and to juveniles. They are also valuable feeding areas, as they are rich in plankton, and small invertebrates and algae grow over the seagrass leaves.

There are ~100x more animals sheltered and feeding on a seagrass meadow than in the adjacent sandy-bottomed areas without vegetation.

On a global level, seagrass supports ⅕ of the 25 most important fisheries (2).

In the Sado estuary seagrass beds support emblematic species with economic value to traditional fisheries - cuttlefish, gilthead seabream, seabass, sole - and charismatic species, important for marine conservation and tourism, like seahorses and the resident population of bottlenose dolphins.

©Nuno Farinha

1. Long-snouted seahorse (Hippocampus guttulatus)

2. Seagrass (Cymodocea nodosa)

3. Spider crab (Maja brachydactyla)

4. Thin lip mullet (Liza ramada)

5. Golden grey mullet (Liza aurata)

6. Cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis)

7. Mussel (Mytilus edulis)

8. Ray egg capsule

9. Flat top shell (Gibulla sp.)

10. Limpet (Patella sp.)

11. Finger-shaped sea pen (Veretillum cynomorium)

12. Moon jelly (Aurelia aurita)

13. Bladder wrack (Fucus vesiculosus)

14. Common octopus (Octopus vulgaris)

15. Two-banded seabream (Diplodus vulgaris)

16. Blackspot seabream (Pagellus bogaraveo)

17. Pouting (Trisopterus luscus)

18. European eel (Anguilla anguilla)

19. Alface-do-mar (Ulva lactuca)

SEAGRASS MEADOWS ARE CRUCIAL ECOSYSTEMS IN STRATEGIES TO COMBAT THE CLIMATE CRISIS AND ONE OF THE MOST POWERFUL NATURAL BLUE CARBON SINKS

More than half of all carbon present in the atmosphere (55%) is fixed by marine organisms - the blue carbon. These organisms range from bacteria and plankton to seagrass, saltmarshes and mangroves. The vegetated coastal ecosystems - seagrasses, saltmarshes and mangroves - are the main blue carbon sinks of the planet. They occupy less than 1% of the seabed, and contribute to more than half (50 to 70%) of all carbon storage in the ocean.

Seagrass meadows have a high carbon sequestering rate, with an average of 830 Kg of carbon per hectare per year (3), about 30x higher than terrestrial forests (4).

They represent only 0.05% of terrestrial plant biomass, but they store an equivalent amount of carbon per year, which makes them one of the most efficient carbon sinks on the planet (4).

Blue carbon can remain stored in sediments for millenia, unlike carbon sequestered and stored by terrestrial ecosystems, which only remains for decades or centuries before returning to the atmosphere.

THE 3RD MOST ECONOMICALLY VALUABLE ECOSYSTEM!

Seagrass meadows are one of the most valuable ecosystems on Earth for the services they provide. The economic value (natural capital) of seagrass meadows was evaluated as higher than 25,000€ per hectare per year, just considering the nutrient cycling service (5). This is particularly relevant regarding the nitrogen cycle, one of the essential elements to primary production, on which depends good water quality; seagrass promotes purification of water by using nitrogen from urban and agricultural effluents. A study on Ria Formosa concluded that each hectare of seagrass meadow (Zostera noltei) removed 510 tons of nitrogen from the seawater each year (6).

©Nuno Farinha

SEAGRASS meadows ARE DECLINING BUT THEY CAN RECOVER

Seagrass meadows have been disappearing worldwide due to human-related causes, so they are considered to be vulnerable and endangered habitats (1). They are declining due to unsustainable use of coastal areas.

Studies show we are losing 1.5% of seagrass meadows worldwide per year, which is equivalent to the disappearance of 2 soccer fields per hour (since 1980) (10).

The major threats include:

Direct damages to leaves and rhizomes caused by destructive fishing techniques (bottom trawling, intensive bait digging with rakes and shellfishing with scuba gear) and uncontrolled anchoring;

Burial and increased turbidity of water column caused by dredging in estuaries and lagoons;

Water contamination by urban, industrial and agricultural effluents, which cause eutrophication and may stunt plant growth;

Construction of coastal infrastructures, like harbours, marinas and aquaculture facilities;

More frequent high energy events (storms, floods, heatwaves) associated with climate change.

©Nuno Farinha

RECENT STUDIES ALSO SHOW THAT THIS DECLINE CAN BE REVERTED THROUGH ADOPTION OF MANAGEMENT MEASURES TO STOP THEIR DEGRADATION (7,8). RECOVERING AND RESTORING DEGRADED SYSTEMS IS POSSIBLE AND HAS HIGH ECONOMIC REVENUE POTENTIAL (9), ALLOWING THE RETURN OF THE SERVICES AND BENEFITS SEAGRASS MEADOWS PROVIDE US.

References:

1. Cunha et al., 2011. Seagrasses in Portugal: A most endangered marine habitat. Aquatic Botany

2. Unsworth RKF et al., 2018. Seagrass meadows support global fisheries production. Conservation Letters

3. Fourqurean JW et al., 2012. Seagrass ecosystems as a globally significant carbon stock. Nature Geoscience 5, 505–509.

4. Mcleod E. et al., 2011. A blueprint for blue carbon: toward an improved understanding of the role of vegetated coastal habitats in sequestering CO2.

5. Costanza et al., 2014. Changes in the global value of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change 26 152-158

6. Alexandre et al., 2012. Inorganic nitrogen uptake kinetics and whole-plant nitrogen budget in the seagrass Zostera noltii. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 401 7-12

7. de los Santos, C.B. et al., 2019. Recent trend reversal for declining European seagrass meadows. Nature Communications. 10:3356.

8. Sousa, A.I. et al., 2019. Blue Carbon stock in Zostera noltei meadows at Ria de Aveiro coastal lagoon (Portugal) over a decade. Scientific Reports, 9:14387.

9. Oreska M.P.J. et al., 2020. The greenhouse gas offset potential from seagrass restoration. Scientific Reports, 10: 7325.

10. Waycott, M. et al., 2009. Accelarating loss of seagrasses across the globe threatens coastal ecosystems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106:12377-81